Your First Writing Draft: Typed or Handwritten?

I’m working on my first book-length memoir. It’s terrifying. The general theme or topic: My immigration, at age 24, to America. Rather than just a ME-moir, I blend the personal narrative with national and family history, economics and psychology to examine the socio-economic, feminist and spiritual factors that made me (and 200,000 other young 1980s Irish) leave my own country.

Depending on what gets to stay in there, I’ve written about 75 pages.

Fifty of those pages are well-polished keepers, though a literary agent or editor might have other ideas. Mostly, I wrote and re-wrote those first 50 pages early in the morning, before leaving for work, on a laptop. I just sat there, half asleep and clacked away. These first 50 pages have taken me to that plot point where I’ve gotten my U.S. visa, I’ve filled in some back story (the why I left), I've said my goodbyes and I’ve hoisted my backpack on my back to leave for the airport and my transatlantic flight.

Then (cue the creepy music), it was time to generate new stuff, as in, a lot of new stuff, as in, the first few chapters of the American part of the story.

Oh hell. I tell you, nothing, not even shopping for last year's bathing suit, was as scary.

So I did the adult thing: I found a nice big pile of sand and stuck my head as far into it as I could without actually ingesting sand or suffocating myself to death. Oh, I didn't quit writing. Nope. I just found other oh-so urgent, must-do projects, so I could procrastinate on what I really needed to do: those first American chapters.

I don't know why I was so frightened. Mostly, when I drafted them in my head, I felt a terrible sorrow, a mother-lion protectiveness in which I wanted to take that young emigre (me!) and lead her by the hand and protect her from all the things she didn't, couldn't possibly know. More, I wanted to give her a sense of and pride in herself and, most important, the chutzpaha to assert that self.

Ah, middle-aged revisionism.

Then, one morning last week, I got myself up out of bed with, “Just get to it, and stop these damn excuses."

So I switched on my laptop. I must say, it's a very nice laptop. And it has this super, beautiful Facebook app and Twitter and email and ... (more procrastination).

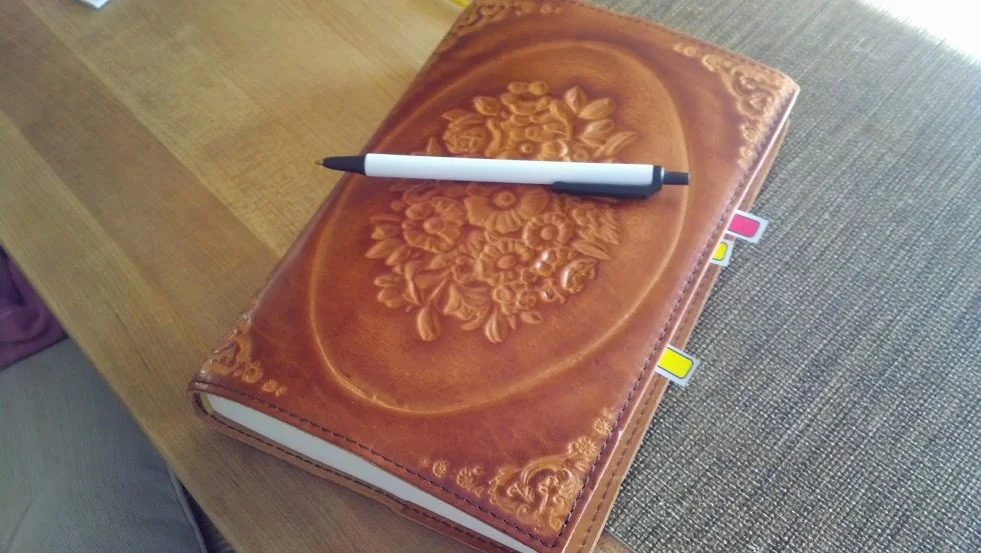

Then, thoroughly fed up with myself, I shut off the laptop and opened up my brand new journal, a well-chosen birthday gift from a great writer friend.

My hand stopped shaking.

America, at least via pen and paper, lost its scare factor. In fact, I am amazed by what this handwritten draft is unearthing, what I am managing to remember from 27 years ago. I am equally shocked to discover what the older, middle-aged me thinks about those early American years and my own immigration. Would all this memory and wisdom have come as easily in a typed first-draft?

Memory and wisdom.

I'm glad to say that there's a good chunk of both there now, in black (pen) and white (paper).

Do you type or hand-write your first drafts? Does it depend on the topic, in that certain subjects lend themselves to keyboard, while others absolutely must be journaled or hand-written?