“Just Do Your Own Work:” On the 10th Anniversary of Séamus Heaney’s Death

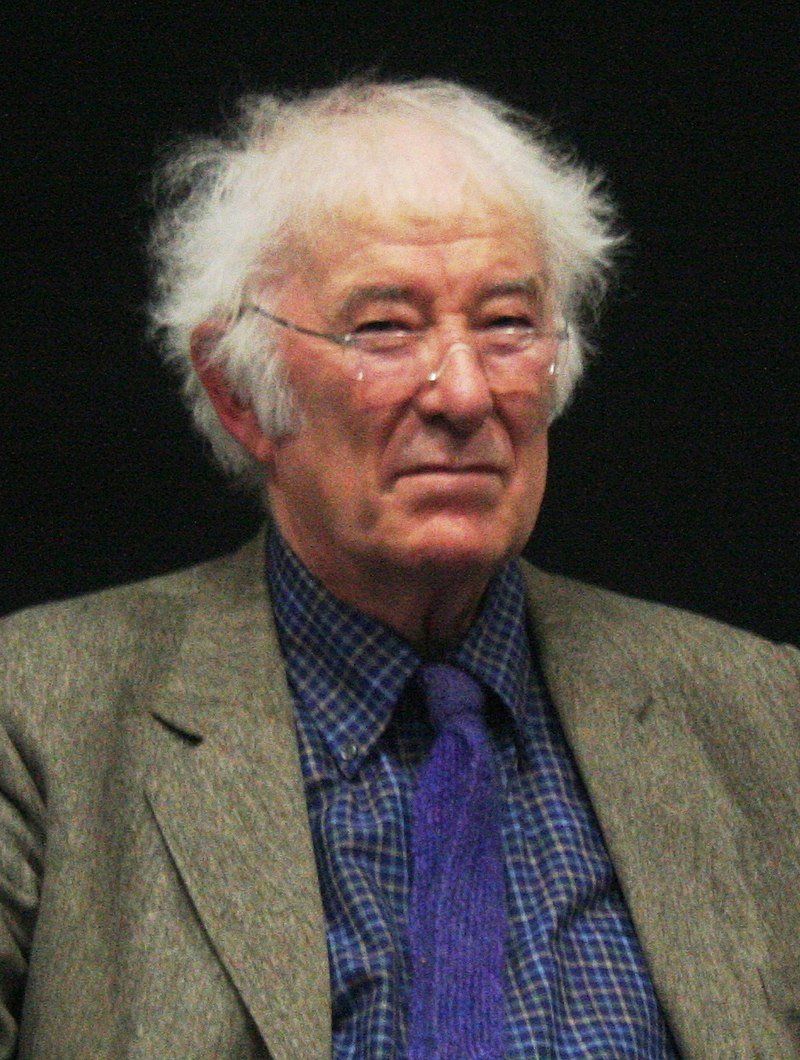

Photo credit: Sean O’ Connor, 2009

As a 17-year-old undergraduate student in Dublin, I was lucky enough to have Séamus Heaney as my professor and the chair of our college English Department.

It’s funny the things you remember about someone. In addition to his poetic talent and genuine kindness, Séamus Heaney was the first man I ever saw wearing western-styled cowboy boots. Also, he could tell a great, great story—mostly about rural life in Ireland.

One day, I remember him telling this long scéal about a farmer who dithered about whether he should or shouldn’t go across the fields to knock on a neighbor’s door to borrow a shovel.

As a rural kid, who felt outclassed and intimidated by that south Dublin campus, I hung on Heaney’s every word. By story’s end, I think I was the only student in that classroom laughing my head off and longing to hear more.

Now, almost 40 years later, here I sit here in America, where, on the 10th anniversary of Mr. Heaney’s death, I can still hear him reading Beowulf to us in that second-floor classroom. On that day, I was far too young and definitely too immature to appreciate my own privilege.

Writing Advice That Lives On

Long after I graduated, in two separate media interviews, Séamus Heaney gave some writer advice that resonated with me back then and, to this day, has become a kind of touchstone for my own work.

First, just before he was awarded the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature, I read an interview in some magazine in which he spoke about his then-dual life as a working professor and as one of the world's greatest modern poets.

Back then and now, as a writer with a day job, I loved the part of the interview where he stated that he had always considered it his first duty to earn a living and provide for his family.

Later, in a separate interview, Heaney told the reporter that, as a writer, we shouldn’t let ourselves get distracted by—or compete with—other writers. Instead, Heaney counseled, “just do your own work.”

Speaking of work, read Heaney’s poem, “Digging” at the website of The Poetry Foundation. Earlier this summer, when I was invited to recite or read a poem for our local “Favorite Poem” event, “Digging” was my automatic choice—though, of course, I could never read it like the master poet and reader himself.

Listen to the Nobel Laureate poet recite “Digging” here.

Rest in peace, Séamus Heaney, (1939- 2013).